Share this article

The Little Sparrow and The Little Flower

The world is not divided into good and bad, but into those who love and those who do not love.

Now and then, God sends extraordinary people to our world who, when they die, act as a bridge between heaven and earth. In most religions, they are known as saints, and people pray to them for help in challenging situations. But others, including those who consider themselves ‘spiritual but not religious,’ cannot relate to these holy beings. Though they hunger to hear messages of transcendence, stories of divine hope, the mystical and the miraculous, they go about their daily lives feeling remote at best from the ranks of those they see as too saccharine and impossibly virtuous. However, they might be relieved to know that many saints were far from perfect. Some of them led lives of self-indulgence, even decadence, before their hearts were converted. Perhaps that’s why those considered by society as notorious and outsiders can relate to them.

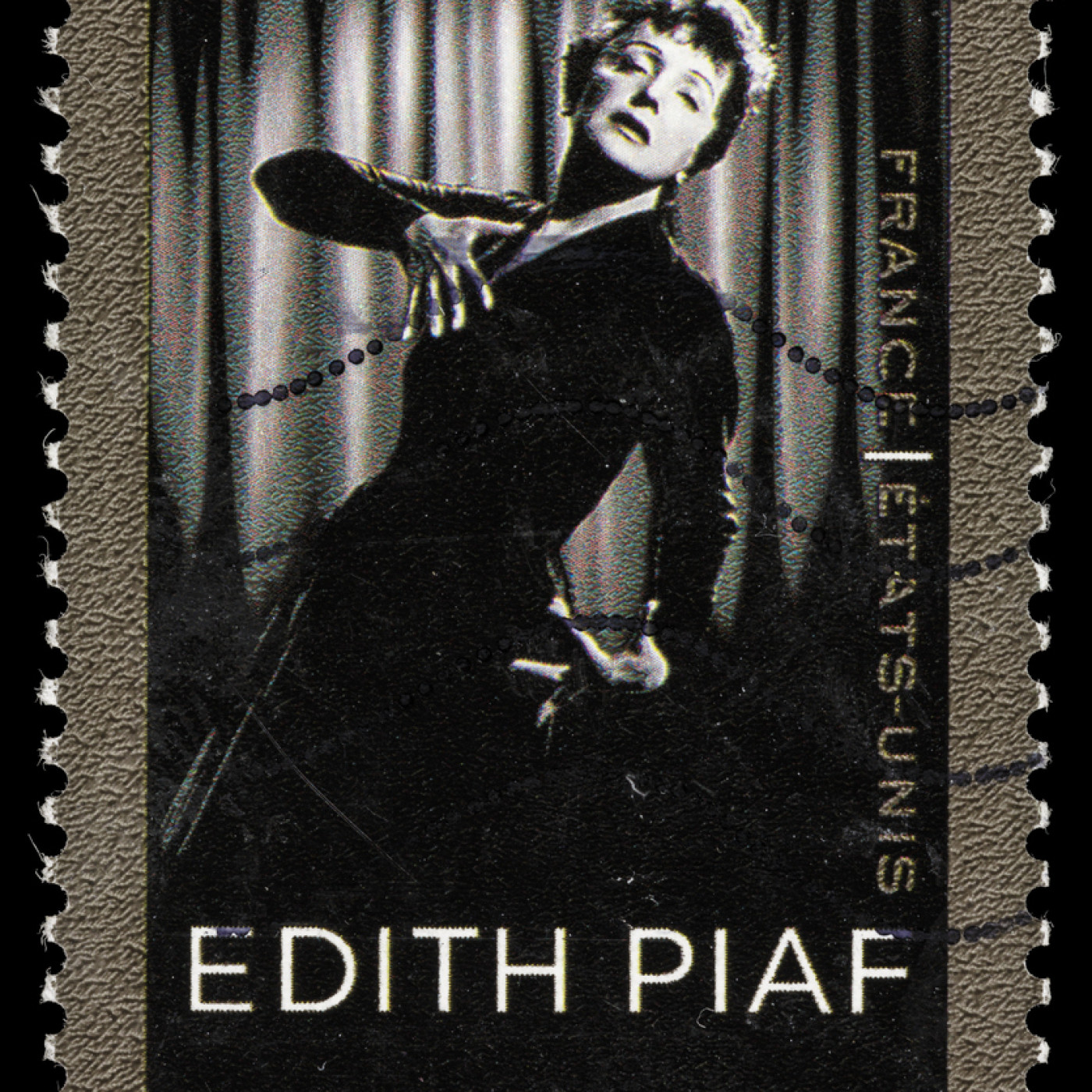

One such outsider was Edith Piaf, the world-famous singer who led a life so bohemian and scandalous that she makes a modern-day ‘wild child’ look like a calculable conformist. She was an alcoholic and a drug addict who had many lovers. Yet, contrary to what one might expect, no one was more devoted to St. Thérèse than Edith Piaf. From early childhood until her death at age 47, she regularly prayed to her fellow Frenchwoman, St. Therese of Liseux or ‘The Little Flower’ as she is also known.

On the surface, Edith may have shared little in common with Thérèse: they came from radically different backgrounds and lived lives that couldn’t be more different. But despite experiencing the highs of fame and the lows of addiction, poor health, and tremendous sadness, she always placed love at the centre of her life, just as Thérèse had done. Looking at both women’s backgrounds might give us a clue why this was the case:

St. Thérèse of Lisieux (1873-1897)

Thérèse was born into a middle-class, loving Catholic family. In her famous autobiography, Story of a Soul, she recalled the idyll of her early childhood, spent with her parents and five sisters in the unspoilt French countryside. Her father, Louis Martin, was a relatively prosperous jeweller and watchmaker, but eventually sold his watchmaking shop to assist his wife, Zélie, in her even more successful lacemaking business.

Contrary to her reputation, the saint was born with a violent nature. ‘She flings herself into the most dreadful rages when things don’t go as she wants them,’ her mother recalled. Thérèse corroborated her mother’s statement, admitting in her autobiography that her temperament could easily have led her to grow up to ‘become very wicked’ if she hadn’t had such good parents who helped her overcome it. (Both parents were exceptionally pious and were canonised by Pope Francis on October 18, 2015). She also suffered from depression, scruples (a causeless feeling of guilt), and extreme sensitivity. However, she believed in God’s love for her and reports in her autobiography that on Christmas Eve, 1886, she was cured of her hypersensitivity. She then moved away from excessive self-preoccupation, accepted others into her life, and became interested in other people’s lives.

Thérèse felt an early call to religious life, and at 15, she joined two of her older sisters in the cloistered Carmelite community in Lisieux, Normandy. In 1895, she became ill with tuberculosis and endured great suffering for nearly two years before her death, aged 24. During this time, she also suffered a trial of faith, which she offered to God so that ‘the bright flame of faith’ could shine for those who do not believe.

Thérèse had died in obscurity, but soon after, Story of a Soul was published and became a worldwide bestseller. In her book, she says that she believes that it isn’t necessary to accomplish heroic acts or great deeds to attain holiness and express her love of God: ‘Love proves itself by deeds, so how am I to show my love? Great deeds are forbidden to me. The only way I can prove my love is by scattering flowers, and these flowers are every little sacrifice, every glance and word, and the doing of the least actions for love.’ Her philosophy was later known as The Little Way.

Before her canonisation in 1925, her reputation for goodness and the ability to work miracles spread throughout France. When the First World War broke out, St. Thérèse appeared forty times to soldiers on various battlefields in France. The soldiers said she spoke to them matter-of-factly, resolved their doubts, helped them overcome their temptations, and calmed their fears. Thousands of these French soldiers carried her photo and invoked her as ‘my little sister of the trenches,’ ‘the shield of soldiers,’ ‘the angel of battles, ’ and ‘my dear little Captain.’

Edith Piaf (1915-1963)

‘In the evening of life, we will be judged on love alone.’

⸻St. John of the Cross

Before meeting my late wife, Cushla, I had heard some of Edith Piaf’s songs, including the immortal international hit, ‘Non, Je ne regrette rien’ (‘No, I Don’t Regret Anything’). But it was after we got married that I got to know more about the singer. Being a Francophile, Cushla was a fan of some classic French pop singers, including Patrick Bruel and Johnny Hallyday, but I think Piaf was her favourite.

She had Piaf’s entire record output, which she listened to regularly, especially in the kitchen. Popping in to pour myself a coffee, I’d stop dead to listen, moved by Piaf’s powerful and aching tone, a trembling alto wail that became the voice of the Paris working class. Cushla would interpret some of the lyrics for me, which seemed to reflect the tragedies in Edith’s own life. Fascinated, I wanted to get to know her more.

In 1916, a year after she was abandoned at birth by her mother, a coffee house singer and circus performer, Edith’s father took her from Paris to Normandy, where his mother ran a brothel. There, prostitutes helped look after her. Edith was blind due to inflammation of the corneas from age three to seven. One story goes that she recovered her sight after her grandmother’s prostitutes pooled money to accompany baby Edith on a pilgrimage to Lisieux, the birthplace of Saint Thérèse. By some accounts, the child’s vision was restored within days of this trip. Other versions of the story say the women visited Lisieux in thanksgiving for prayers answered after a cure had been effected. Whichever story is true, Edith began a lifelong devotion to St. Thérèse. She wore the saints’ medal around her neck for the rest of her life and brought her friends and lovers to The Little Flower’s grave in Lisieux. She also kept a little statue of Thérèse on her night table at home and in her stage dressing room. Before each concert, she prayed to her favourite saint, saying, ‘Thérèse, I sing for you!’

However, it was far from concert halls that Edith began her singing apprenticeship. She first started to perform in public at age 14, when her father took her with him as he travelled all over France, giving acrobatic street shows. In 1932, nightclub owner Louis Leplée discovered her as she sang on a street corner in the seedy Pigalle area of Paris. He persuaded her to sing at his club, Le Gerny’, located off the more elegant Champs-Élysées. There, her small stature inspired the nickname that would stay with her for the rest of her life and serve as her stage name: La Môme Piaf (Parisian working-class slang meaning ‘The Waif Sparrow’ or ‘The Little Sparrow’). Her performances were legendary, and soon she was in great demand as France’s most famous entertainer, assisting and paving the way for the arrival of other French household names, including Yves Montand and Charles Aznavour.

As regards her personal life, Edith knew love. Still, she also had more than her fair share of sadness, as husbands and lovers either left her or were killed. The love of her life, the French world champion boxer Marcel Cerdan, who had once joined her on a visit to Thérèse’s grave in Lisieux, died in a plane crash in October 1949 while flying from Paris to New York City to meet her.

Despite a glittering career, tragedy never seemed far away in Edith’s life. The hard-living years of alcohol and drug abuse, exacerbated by a series of car accidents, eventually took their toll on her health. Writing down her life story on her deathbed in the hospital, she asked people and God to think of her with the Saviour’s words said of Mary Magdalene: ‘Her sins, which are many, are forgiven; for she loved much.’

After suffering liver failure and an aneurysm on October 10, 1963, the little sparrow took her last breath at age 47. I like to think her friend, the Little Flower, who had died in 1897 at age 24, was at her side as she passed from this ‘veil of tears’ into her new life in paradise.

Share this article

Categories

in your inbox

Hope